The IT Strategy Playbook (Part 1): Define, Shape, Deliver

How CIOs, CTOs, and senior technologists move from activity to outcomes by closing four recurring gaps.

This article is Part 1 of Deep Engineering’s exclusive ongoing series adapted from The IT Strategy Playbook: How CIOs and CTOs can drive business growth through focused action, architecture, and execution by (Packt; publishing May 2026). Millett is an IT leader, strategist, and author with 25+ years’ experience, having served as a CIO, CTO, and architect leading large-scale transformations and shaping IT strategy across sectors. He has authored several books on software architecture and IT leadership, and speaks and writes frequently on bridging business and technology.

Each installment is a light, web‑ready adaptation of an original chapter submitted by Millett, giving readers the opportunity to preview the knowledge that will be included in the final book. In return, we invite you to leave constructive feedback to improve the book and the chapter in the comments below and follow Millet on this adventure.

Let us begin.

“The main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.” — Stephen Covey

If you’re a CTO, CIO, or IT leader, you’ve probably been told to “be more strategic” and “align with the business.” That’s easier said than done. We’re experts in technology, but many of us lack the mental models to turn abstractions like strategy and digital transformation into actionable plans. When the board or CEO asks for a long‑term roadmap that shows how technology enables growth, we’re left wrestling with vague terms and questions we were never taught to answer.

Even when a technical plan exists, we often fail to articulate it. Communication either dives too deep into detail or floats into abstraction. The result is the same: we don’t explain technology choices in a way that shows how the business competes and wins.

This gap—between creating a strategic plan and communicating it—sits at the heart of this article. What follows is the moment that forced a shift from running systems to defining direction, shaping architecture, and delivering strategic impact, and the journey that led to the framework at the center of this work.

The situation

I joined a company as its first IT Director and immediately entered a due‑diligence process. Three months later we were acquired by a private‑equity owner. The process was intense, but it provided a deep understanding of databases, infrastructure, security, risk, applications, and the team. The IT landscape wasn’t perfect—no company’s ever is—but it felt manageable.

Then came the Tuesday morning email: “The 100 Day Plan.” Among the requests:

“We need a comprehensive IT strategy aligned with our growth objectives. Present initial thoughts next month, with a full strategic plan in 100 days.”

The complication

I knew technology inside out. Strategy—linking technology to business goals—was another story. Like many would, I turned to Google. Frameworks, templates, and roadmaps abounded, but they felt generic and disconnected from our situation.

I produced a polished deck, full of technology roadmaps, maturity assessments, and investment priorities.

In the boardroom, the CEO flipped through the pages and paused.

“This all looks thorough,” he said. “But what problem are we trying to solve?”

I froze. I had built a deck of technology solutions without defining the problems they solved—outputs, not outcomes. Activity, not impact. I was being seen exactly as presented: a capable technology manager outlining projects, not a strategic leader proposing investments to deliver impact. There was no visible link between technology investment and business outcomes.

Figure 0.1: The gap between technology output and business impact

The question

That single question—What problem are we trying to solve?—exposed deeper challenges:

How does an IT leader become a strategic leader?

How do you connect technology to competitive advantage—in practice, not theory?

How do you explain those connections so boards and executives immediately understand?

These became the guiding focus.

The answer

IT strategy is business strategy. Every technology decision is a business decision about how the organization competes, operates, and delivers value. Consolidating systems across brands isn’t just integration; it’s a choice about whether to compete as one company or many. Investing in real‑time analytics isn’t just faster reporting; it’s enabling dynamic, personalized pricing that affects competitiveness and margins.

Most IT leaders struggle to make that connection. We know the technology, but not always how to translate it into advantage. That struggle appears as recurring structural gaps that make it impossible to answer the CEO’s question. Left unaddressed, they lead to outputs without outcomes—technology choices that don’t create business impact.

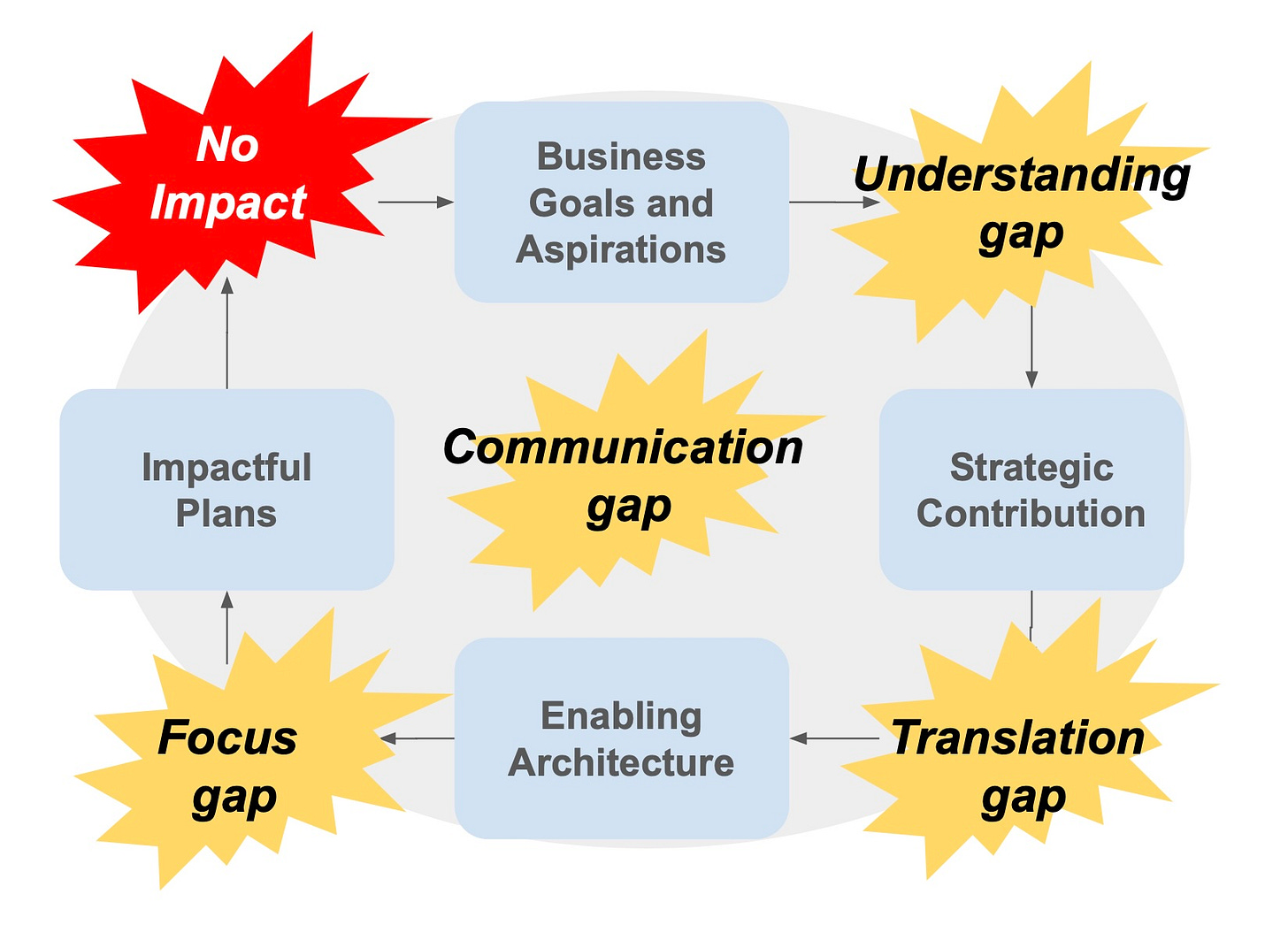

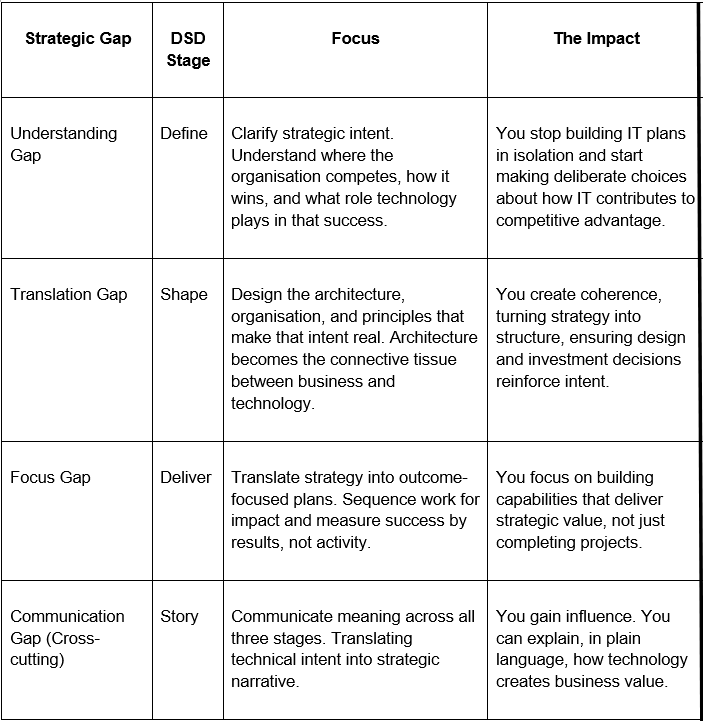

The four gaps:

The Understanding Gap: The disconnect between business goals and IT’s strategic contribution. This is the inability to answer “What problem are we trying to solve?” and to tie IT choices to how the business competes and wins.

The Translation Gap: The disconnect between IT’s strategic contribution and the enabling architecture. High‑level intent never becomes coherent design, resulting in fragmented, fragile systems.

The Focus Gap: The disconnect between enabling architecture and impactful plans. Investments aren’t prioritized by measurable strategic impact, producing sprawling, low‑value project portfolios.

The Communication Gap: The inability to clearly communicate strategic intent, architectural vision, and execution plans. This multiplies every other failure by eroding buy‑in and funding.

Together, these gaps break the link between IT action and business success: strategies that look impressive on paper but don’t change results; delivery plans that are busy but directionless. Closing them transforms IT leadership—from order‑taking to shaping direction, driving advantage, and turning outputs into outcomes.

Figure 0.2 — The four gaps that lead to a lack of business impact

Closing the Gap

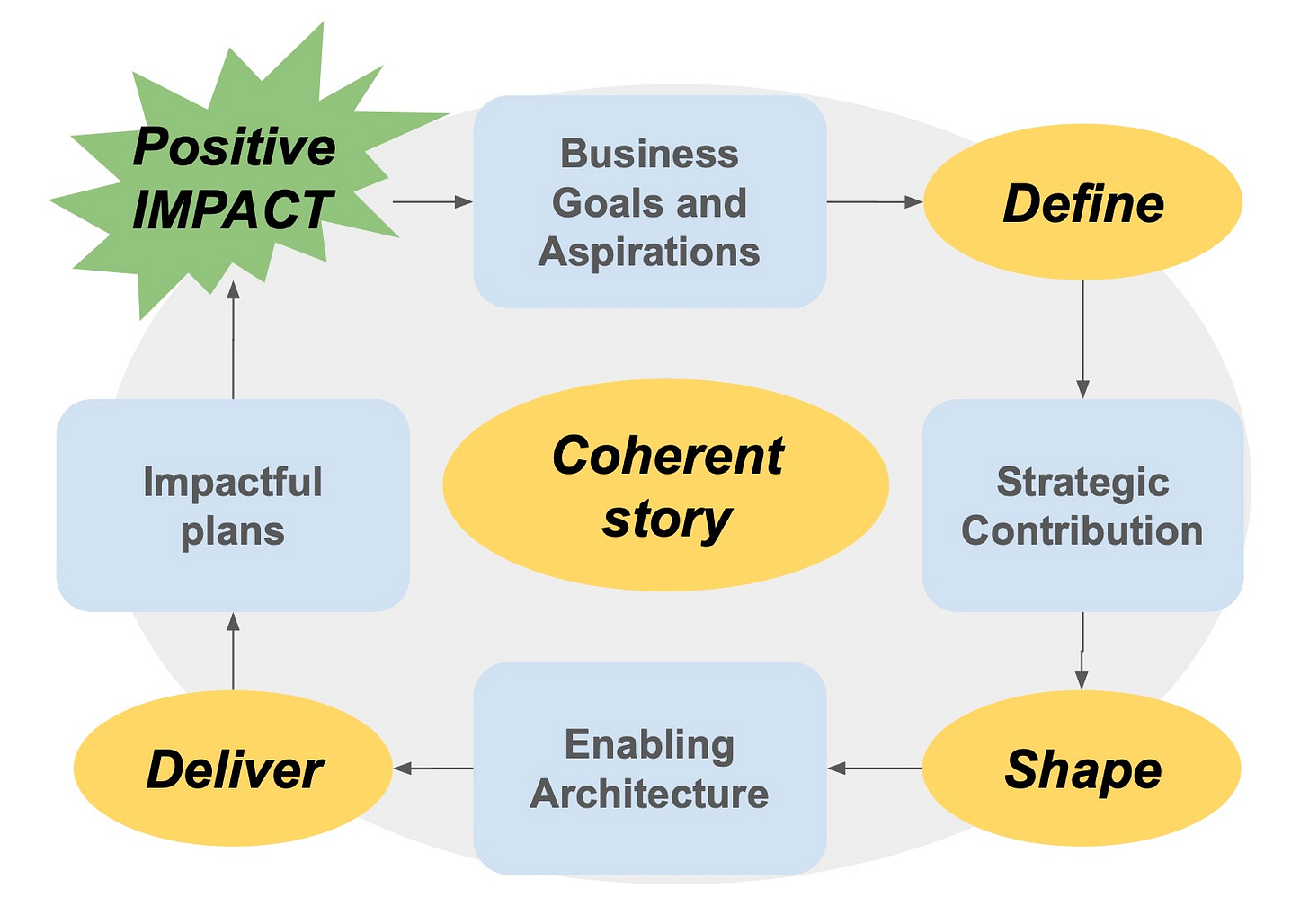

That boardroom moment made something clear: a better presentation wasn’t enough; a better way of thinking was needed. I began sketching how strategy, architecture, and planning connect. Over time—across board presentations, diligence cycles, acquisitions, and strategy sessions—that evolved into the DSD Loop: Define → Shape → Deliver. It is a practical way to connect strategy, architecture, and planning through a consistent story, ensuring the CEO’s question can be answered at every stage.

Figure 0.3 — Addressing gaps using the Define–Shape–Deliver Loop to deliver business impact

Table 1: The DSD loop and its impact

Why this approach works

The challenge isn’t intelligence or effort; it’s starting in the wrong place. When you define business intent first, shape architecture second, and deliver last, you stop reacting and start directing. You move from “What do you need from IT?” to “Here’s how technology will help us win.”

The DSD Loop deliberately puts delivery last because many failures start with technology first. That thinking leads to “AI is the solution; now find a problem,” or building data platforms before deciding which decisions data should inform. Start with intent, then shape the architecture, and delivery becomes straightforward—the red thread links every technical choice to a strategic outcome.

Who this is for

CIOs/CTOs seeking to be seen as strategic enablers, not cost centers.

CEOs/COOs who know digital transformation is essential but need signal over noise.

Consultants who help clients cut through complexity.

Students and practitioners who want to see how technology and business strategy intersect.

This approach won’t hand over a magic formula or prescribe specific technologies. Context matters. What it offers is a way to strengthen critical thinking, creativity, problem‑solving, leadership, and influence—so outcomes improve.

Why listen

This is grounded in lived experience: the Tuesday email, the frantic searching, the hollow slide deck, and the CEO’s question. Since then came boardrooms, due diligence, investor conversations, and most importantly, consistent business impact—paired with deliberate study of how strategists frame choices, tell stories, and create results.

How the book and series is structured

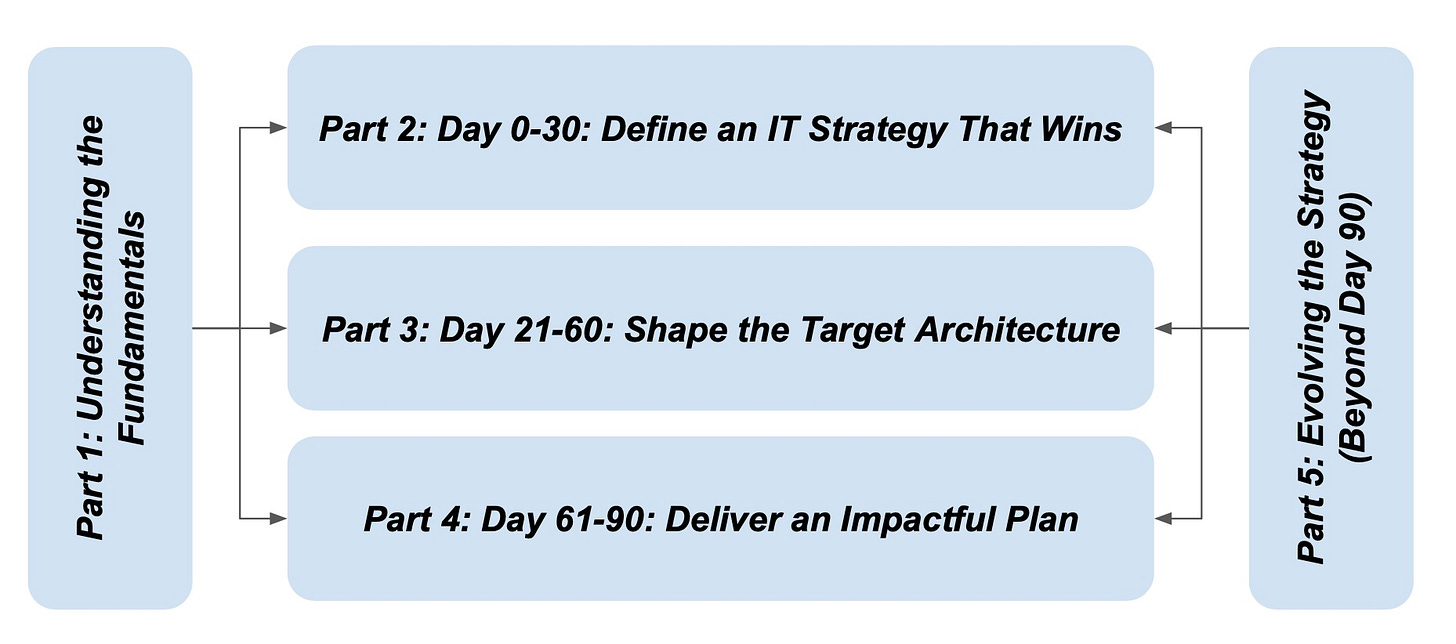

Figure 0.4: What you will learn by the end of the book and series

We’ll walk from a standing start to strategic momentum by Day 90, unpacking each stage of the DSD Loop. The techniques aren’t new inventions; they’re proven patterns used in context so strategic intent flows through design and into delivery.

Part I: Understanding the Fundamentals — Strategy as explicit choices to win; architecture as consequential design for coherence; planning as prioritization anchored to outcomes.

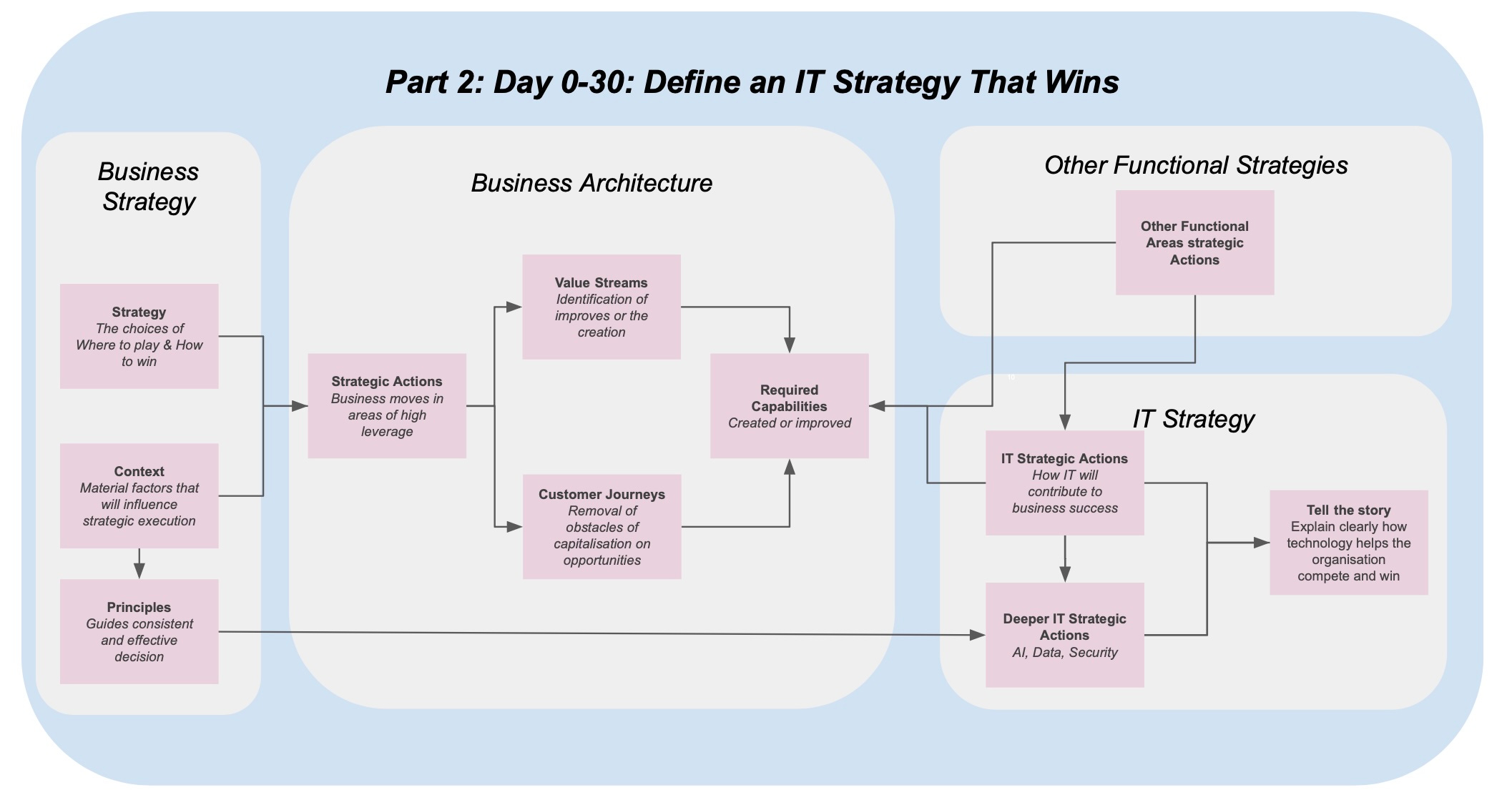

Part II: Day 0–30 — Define an IT Strategy that Wins — Establish the directional why and strategic what; translate business goals into capability enhancements and IT actions; culminate in a communication plan that ties every action to business success.

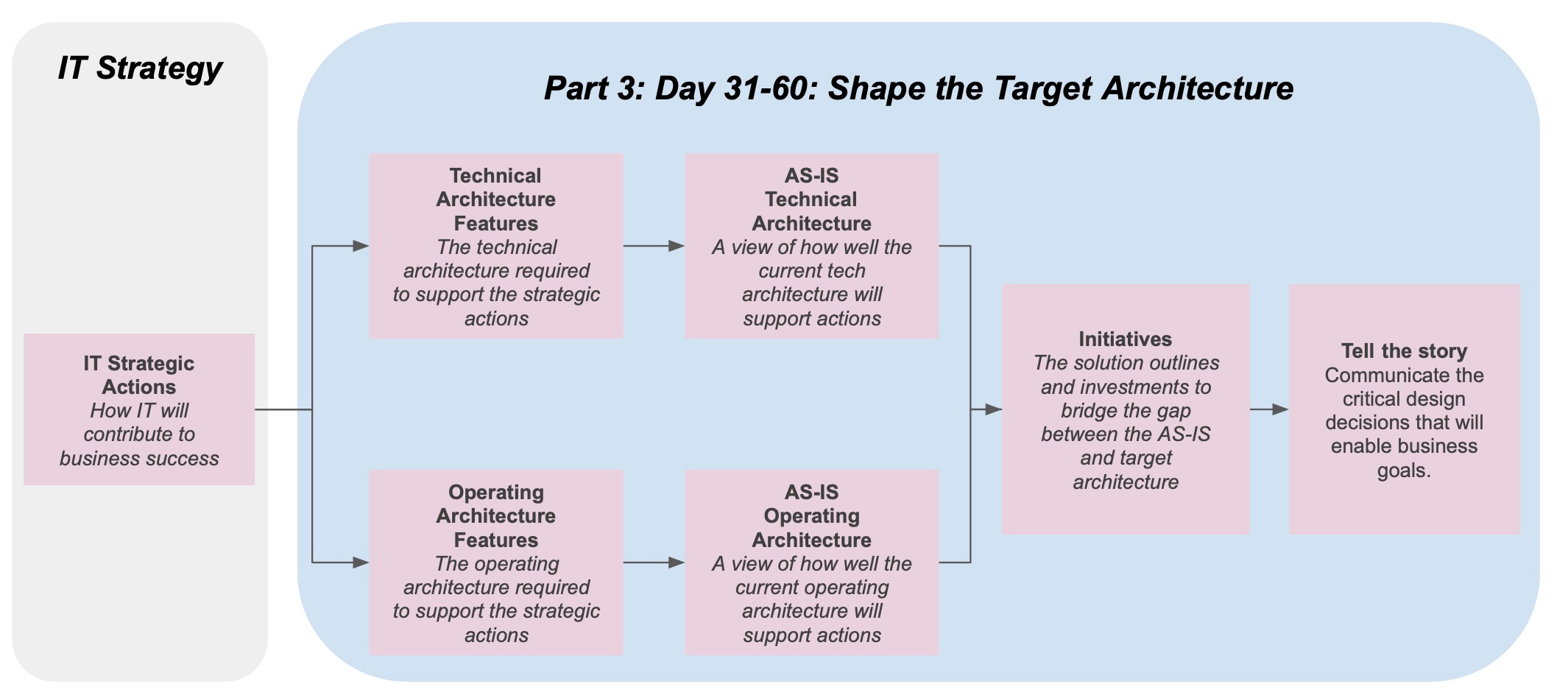

Part III: Day 31–60 — Shape the Target Architecture — Move from intent to socio‑technical design: technology, teams, operating model, and governance; understand the AS‑IS, outline initiatives, and tell the story of value.

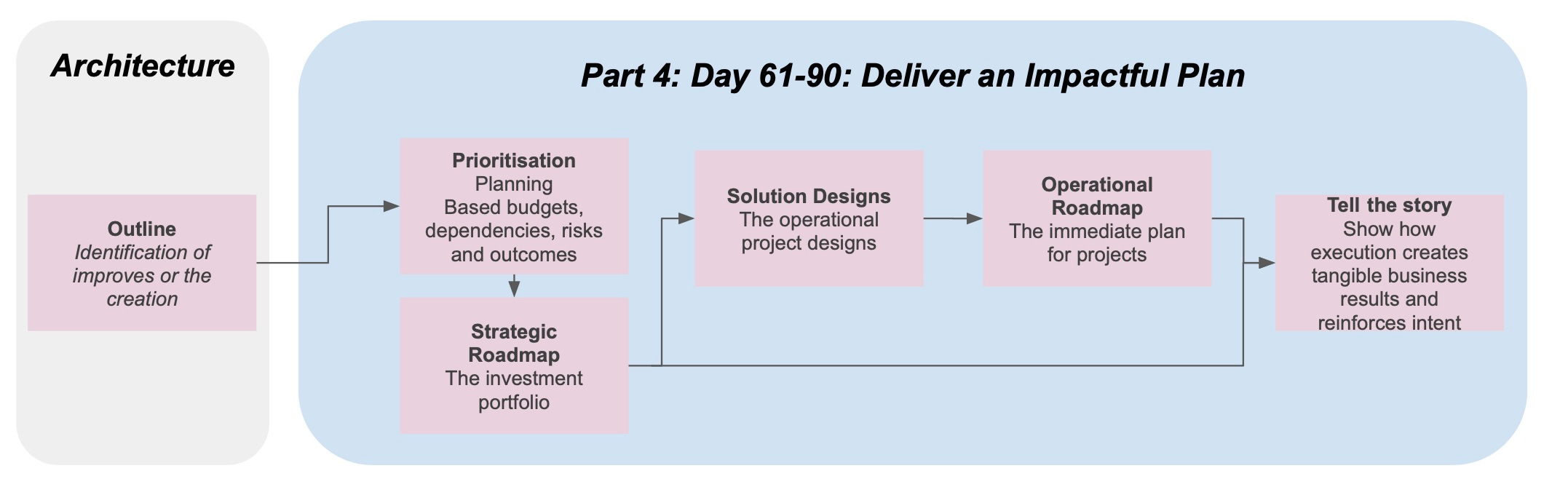

Part IV: Day 61–90 — Deliver an Impactful Plan — Prioritize by value and constraints; form the strategic roadmap and short‑term operational plan; communicate for investment sign‑off by focusing on measurable impact.

Part V: Evolving the Strategy (Beyond Day 90) — Treat strategy and architecture as living; adopt adaptive strategy and evolutionary architecture for continuous planning.

Building Critical Skills for Future Success

Based on the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report (Jan 2025), the most critical skills cluster into four categories:

Cognitive & Problem‑Solving — Analytical thinking, complex problem‑solving, critical thinking, creativity, reasoning.

Technical & Digital Fluency — Technology use/monitoring/control; design and programming.

Interpersonal & Social Influence — Leadership and social influence.

Self‑Management & Learning — Active learning, resilience, stress tolerance, flexibility.

This series emphasizes translating technical strength into strategic outcomes by developing cognitive, interpersonal, and self‑management capabilities. Each phase of the DSD Loop builds the following:

Define (Day 0–30): Critical thinking to structure the problem space; effective communication to secure alignment; creativity to challenge the status quo.

Shape (Day 31–60): Creative reasoning using visual mapping to design enabling architecture; translate technical vision into non‑technical language; active learning to derive coherent, evolutionary design principles.

Deliver (Day 61–90): Analytical prioritization to justify investment; storytelling to close the communication gap and influence stakeholders; resilience to manage ambiguity and maintain roadmap integrity.

How to use this playbook

This is a playbook, not a textbook. The goal is progress, not perfection—guided by the DSD order: Define → Shape → Deliver. Most IT strategies fail by starting with delivery before intent and architecture.

Use it to:

Build a three‑year strategic plan for investment cases and board planning.

Focus on a specific objective (e.g., a new product line, a new market, a new digital service).

Prepare a board presentation that tells a clear story about how technology drives positive business impact.

Whichever path you take, begin with intent, then shape how technology and teams will enable it, and only then plan and deliver the work. You don’t have to perfect everything at once. Identify the next logical step in your Define–Shape–Deliver journey, apply it, learn, and return to refine. Effective strategy evolves through a continuous loop—each cycle sharper and more connected to business outcomes than the last.

Up Next: Beginning with the fundamentals

Before applying the framework, it is important to establish the basics. Most IT strategy failures don’t happen because of technology; they happen because leaders misunderstand what strategy is, how it connects to architecture, and why traditional planning falls short. That’s where we will begin in the next article in the series: strategy, architecture, and planning as practical tools for better decisions.

Scott Millett is refining this series—and the book—as we go. What resonated, what needs sharpening, and what gaps did you spot? Share your thoughts in the comments—we’d really appreciate it