Deep Engineering #31: Sam Morley on decomposition & abstraction in C++

What “future you” needs: How senior C++ engineers make decisions that hold up over time

C++ Memory Management Masterclass (Live) — Jan 24–25

We are back with cohort two of our live, hands-on workshop with Patrice Roy (author of C++ Memory Management, ISO C++ WG21 member) focused on practical ownership models, RAII, smart pointers, exception safety, allocators, and debugging memory issues in production C++ code. Use code DEEPENG50 for 50% off Standard and Bulk tickets (not valid on Premium Pass).

✍️From the editor’s desk,

Happy New Year — and welcome to the first Deep Engineering issue of 2026!

Most senior engineers can solve hard problems. The real test is whether the team can repeat that success—six months later, with new constraints, when “future you” has lost the context that made the design feel obvious at the time.

This issue is Part 1 of a two-part series grounded in our interview with Sam Morley, Research Software Engineer and Mathematician at the University of Oxford and author of The C++ Programmer’s Mindset.

In today’s installment we cover four guiding principles from Morley:

Be explicit about your process

Decompose relentlessly

Treat abstraction as a multi-cost decision

Use the STL as your baseline

We’ve also included the complete Chapter 1: Thinking Computationally from Morley’s book. Our tool of the week today is Tracy, a practical complement to this mindset. In Part 2, we’ll extend the same framing into maintainability under “power tools,” hardware-aware performance, and safer concurrency. You can also watch the complete interview and read the transcript here.

Adopting the C++ Programmer’s Mindset (Part 1) with Sam Morley

Adopting the “C++ programmer’s mindset” means combining sound engineering habits with deep knowledge of the language’s strengths. In this first part, we learn from Sam Morley that senior engineers should actively reflect on how they solve problems, relentlessly break down big challenges, choose abstractions with care, and take full advantage of the rich standard library. These practices lead to code that is not just correct, but also maintainable and efficient by construction. As Morley puts it, it’s about “how you marry [your process] with the C++ language and the broader system to make a better, faster solution.”

Embrace Computational Thinking and Process Awareness

Senior C++ engineers often solve complex problems intuitively, but Sam Morley argues that making this process explicit is key to growth. Morley emphasizes “thinking about your process” – after solving a problem, step back and ask how you approached it.

By breaking down challenges, identifying abstractions, and noting familiar patterns or novel obstacles, engineers can refine their problem-solving toolkit.

This reflection helps avoid repeated mistakes. As Senior iOS Engineer, Jeremy Fitzpatrick also writes, retrospectively analyzing how errors happen – and how you fixed them – is vital to prevent falling into the same pitfalls again. Morley adds that consciously “documenting” your approach (even just mentally) builds a knowledge base you can pass on to junior developers. This mindset shift – from just writing code to analyzing how you write it – turns problem-solving into a teachable, improvable skill.

The C++ programmer’s mindset ties this process to the capabilities of the language and system. Morley notes that experienced devs already use “computational thinking,” but connecting those abstract problem-solving steps with C++’s specific features and the underlying machine can lead to more efficient solutions. In practice, this means considering how C++ abstractions (like classes, templates, or the STL) and system resources (like CPU caches or IO throughput) inform each step of your solution. Adopting this broader perspective – thinking not just about what to code but why and how in context – is what elevates a senior engineer’s effectiveness.

Break Problems Down

A core principle Morley highlights is decomposition: any non-trivial software problem must be broken into smaller parts.

“The notion that one can solve a problem without breaking it down... is kind of folly,” he says.

Even if it happens unconsciously, every big challenge comprises sub-problems. Experienced engineers should do this deliberately and strategically. Some ways of slicing a problem are more efficient than others, so it pays to practice systematic decomposition.

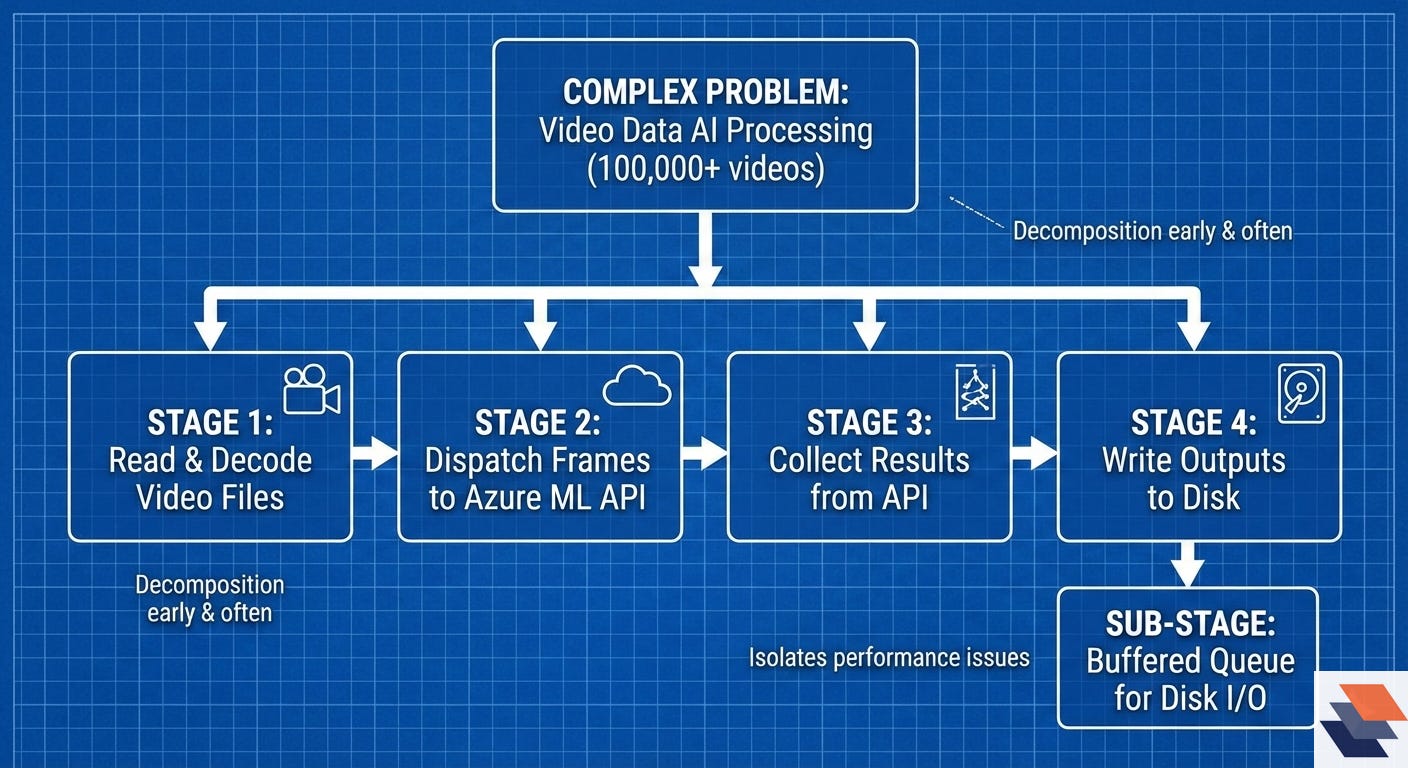

Morley illustrates this with a real-world project processing video data through an AI service. The task – extract frames from 100,000+ videos, send frames to an Azure ML API, then store the results – was obviously too complex to tackle monolithically.

Morley split it into four stages: reading and decoding video files, dispatching frames to the cloud API (with careful rate limiting), collecting the results, and writing outputs to disk. Each stage was further subdivided: for example, the output-writing stage gained a buffered queue to prevent slow disk writes from bottlenecking the faster network responses. This iterative divide-and-conquer approach revealed hidden bottlenecks (disk I/O in this case) and allowed targeted fixes (introducing back-pressure when the buffer grew).

The take-away: decompose early and often. Start with large components, then refine each into smaller, more tractable units until reaching operations you know how to implement (or can leverage from libraries).

This not only makes problems solvable; it also isolates performance issues and enables concurrency where possible. By “bringing down the level of the larger problem to small, atomic things,” you can apply known solutions or standard libraries at each step. Smart problem breakdown is foundational to the C++ mindset – and indeed any engineering mindset – for complex systems.

Choose the Right Abstraction for the Job

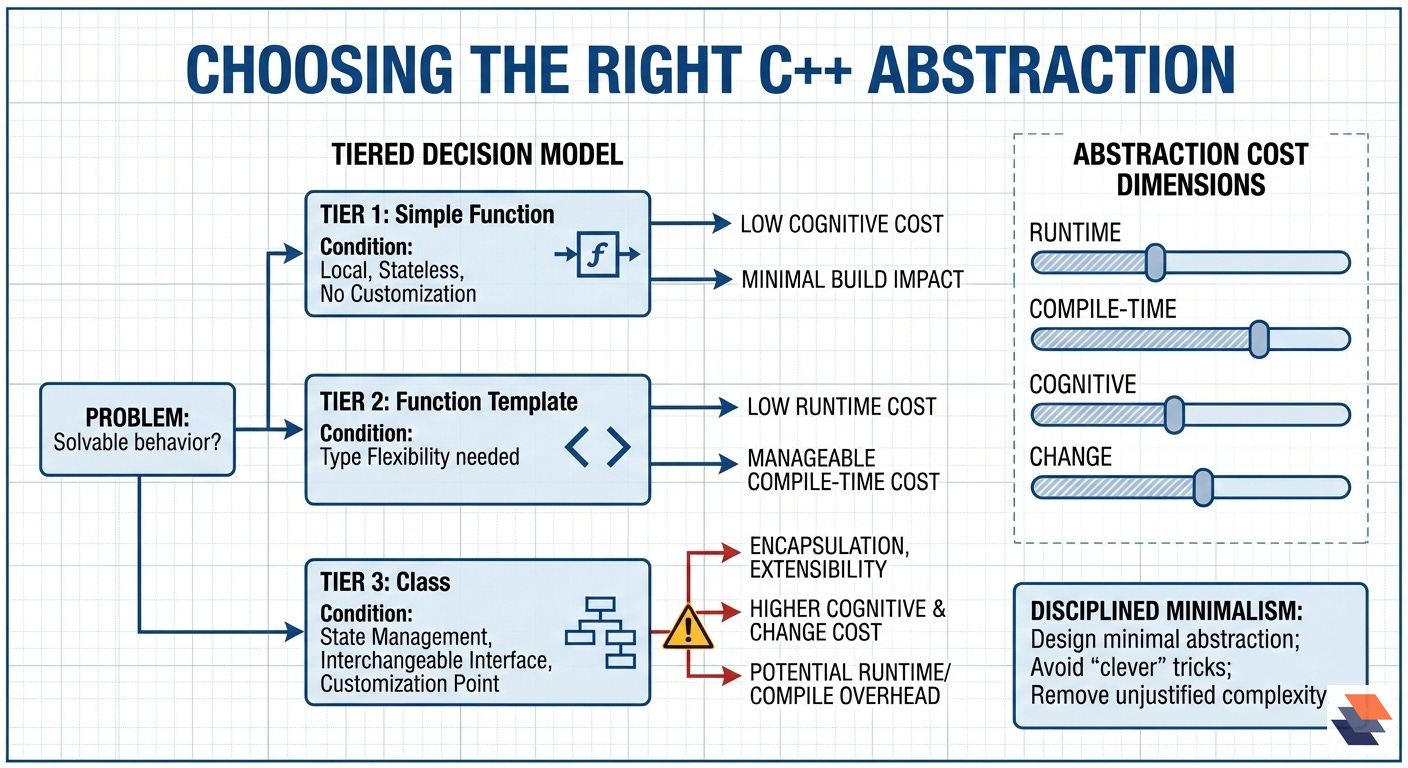

C++ offers many ways to abstract – from simple functions to classes, templates, and beyond – but Morley cautions that no abstraction comes free.

“People claim zero-cost abstractions... They’re really not; every abstraction has a cost,” he says.

This cost may not be at runtime, but could be compile-time overhead or added code complexity. For instance, template instantiations can incur heavy compile-time costs even when they impose little or no runtime penalty. As one accepted definition puts it, zero-cost abstractions in C++ mean “no runtime cost, only compile time cost (the code will be slower to compile)”. In practice, template-heavy code can slow builds and strain developers’ ability to reason about the code. Maintaining a balance is essential.

A useful way to make the trade-offs explicit is to treat “abstraction cost” as multi-dimensional:

Runtime cost: additional instructions, indirection (e.g., virtual dispatch), cache effects.

Compile-time cost: template instantiation, header inclusion blow-up, longer incremental builds.

Cognitive cost: readability, debuggability, and how hard the code is for “future you” (and teammates) to understand.

Change cost: how easy it is to adapt the abstraction when requirements shift (interfaces that are too narrow or too general can both be expensive to fix).

Choosing the appropriate abstraction level

Morley’s rule of thumb is to aim for the simplest abstraction that solves the problem without painting yourself into a corner. In practice, that translates into a tiered decision model:

Start with a straightforward function if the behavior is local, stateless, and unlikely to require customization: This keeps the call site obvious, the code easy to inspect, and the build impact minimal.

Move to a small function template when you need type flexibility at low runtime cost: Morley will template a utility function early if it might be reused with different types, noting that “the cost of doing this is basically nil” in terms of added complexity—provided the template stays small and the diagnostics remain tractable.

Reach for a class only when there is a clear need that a function (templated or not) does not satisfy. Morley’s three “good reasons” are:

State management: you need to encapsulate and protect internal invariants (e.g.,

std::vectormanaging allocation and lifetime correctly).Interchangeable interface: you want a stable outward contract while swapping underlying mechanisms (e.g., reading from disk vs. network behind a consistent

read()/write()API).Customization point: you want controlled extensibility—often via class templates and specialization patterns that are harder to express cleanly with function templates alone.

Classes—especially those using inheritance/virtual functions—bring additional considerations:

Potential runtime overhead (e.g., vtable dispatch) that may be fine off the hot path.

Increased cognitive load (more surface area, invariants, lifecycle, ownership).

More complicated testing and integration if responsibilities are not tightly scoped.

Beware over-abstraction

It is also important to beware of over-abstraction. It’s easy, especially for seasoned C++ engineers, to create elaborate class hierarchies or template meta-programs that technically solve the problem but introduce needless complexity. Every additional layer of indirection or generality can obscure the logic.

Morley’s countermeasure is disciplined minimalism:

Design the minimal abstraction that solves today’s problem.

Treat “clever” template tricks and extra abstraction layers as a last resort, not a default.

When adding complexity, ask: what concrete benefit does this buy—performance, flexibility, or clarity?

If the answer is not specific, measurable, and defensible: remove the abstraction.

Keeping abstractions lean reduces build times and makes life easier for “future you” (and anyone maintaining the code). Morley notes that over-specifying an interface can be just as costly as under-designing one: if an interface is too narrow, you may end up reworking it when the real generality becomes clear.

Leverage the Standard Library and Proven Tools

One practical takeaway that Morley stresses is to use the C++ Standard Library (STL) whenever possible. Reinventing data structures or algorithms that are already well-implemented is usually wasted effort and risk.

“The STL is always there and you can always use it... these are very good, high-performance facilities that make your life easier,” Morley notes.

Using the standard <algorithm> or <vector> isn’t just about saving coding time — it sets a baseline of reliability and portability. Relying on the STL means you spend less time debugging low-level issues or re-optimizing basic operations, and more time on the unique logic of your application.

Mastery of the standard library often distinguishes top-tier C++ developers. Knowing the ins and outs of containers and algorithms allows you to recognize common problems (searching, sorting, transforming collections, etc.) and apply a ready-made solution. This can dramatically speed up development.

Morley points out that using STL algorithms to get an initial solution can reveal where the real performance bottlenecks are — frequently it’s not the standard component itself. In many cases, the out-of-the-box std::sort or std::unordered_map will be sufficient. If not, you have a working baseline to optimize further.

If you do need more specialized tools, there are established libraries like Boost or Abseil. These offer:

Extended containers (e.g., Boost multi-index, Abseil

flat_hash_map)Drop-in replacements with different trade-offs (e.g., small-size optimized vectors)

Google engineers Jeff Dean and Sanjay Ghemawat suggest techniques such as using an absl::InlinedVector (which stores small sequences in-place) for performance-critical code, as this yields gains “without adding non-local complexity” — essentially a free win if your data fits in the small buffer. Knowing about such tools is part of the seasoned C++ mindset: you raise the floor of what problems you can solve effortlessly. Why hand-roll a ring buffer or thread pool when battle-tested implementations exist? The wisdom is to trust well-known libraries for standard needs — and reserve custom implementations for truly novel problems, after asking “why am I re-inventing this wheel?” (Often, you shouldn’t be.)

However, being a good C++ citizen also means keeping an eye on the costs. The STL’s flexibility might not always be optimal for your use case (e.g., std::map might be too slow for very large data if cache misses dominate, where a flat array plus binary search could outperform). Morley’s approach is:

Start with the idiomatic solution using STL or Boost

Measure performance

Iterate based on evidence

Swap in specialized containers/algorithms if needed

But even then, prefer using a well-regarded library implementation over crafting your own. Writing your own containers or memory management is notoriously tricky — a fact Morley underscores. Issues like exception safety, pointer invalidation, and performance tuning of allocations are devilishly complex. “If you are reimagining containers, you should be asking why rather than how,” Morley says. In modern C++ development, leaning on the collective wisdom embedded in the standard library (and its extensions) is a mark of pragmatism and professionalism.

Up Next

Next month, In Part 2, we will delve into additional facets of this mindset: keeping C++ codebases clean and team-friendly, balancing advanced “power tools” like metaprogramming with readability, thinking in terms of hardware (CPU architecture, memory hierarchy) for performance, and strategies for safe concurrency and memory management.

🧠Expert Insight

The complete Chapter 1 from Sam Morley’s book, The C++ Programmer’s Mindset:

Our complete interview with Sam Morley in article and video format:

🛠️Tool of the Week

Tracy Profiler — Real-time timeline profiler for C++ systems

Tracy is an open-source, low-overhead profiler that captures CPU/GPU activity, allocations, and synchronization behavior into a unified timeline view, so you can identify bottlenecks and contention based on traces rather than inference.

Highlights:

CPU profiling with low-friction integration: Direct support for C and C++ (and additional language integrations), designed for instrumented “zones” and practical iteration.

GPU profiling across major APIs: GPU support spans OpenGL, Vulkan, Direct3D 11/12, Metal, OpenCL, and CUDA, enabling end-to-end frame and workload analysis.

Memory and concurrency visibility: Tracks memory allocations, locks, and context switches, making contention and allocation churn observable rather than inferred.

📎Tech Briefs

GitHub Copilot CLI adds “plan mode” and richer agent controls: In a January 21, 2026 GitHub Changelog post, GitHub says Copilot CLI now supports plan mode (toggle with Shift+Tab) plus features like configurable reasoning effort for GPT models and a new

/reviewcommand for reviewing changes directly in the terminal.CodeQL 2.23.9 ships, with a Kotlin deprecation clock starting: GitHub’s January 20, 2026 changelog notes CodeQL 2.23.9 is released (no user-facing CLI/query changes), and states Kotlin 1.6 and 1.7 support is deprecated and slated for removal in CodeQL 2.24.1 (planned February 2026).

Google Cloud Storage introduces “dry run” for batch operations: In Cloud Storage release notes dated January 16, 2026, Google says you can now use dry run mode to simulate Storage batch operations jobs “without modifying or deleting data,” to validate configuration before running the real job.

AWS announces EC2 X8i GA with large-memory specs and published perf deltas: On January 15, 2026, AWS developer advocate Channy Yun announced general availability of EC2 X8i instances, claiming up to 6 TB memory, 1.5× more memory capacity, 3.4× more memory bandwidth, and up to 43% higher performance versus prior-generation X2i instances (with workload-specific figures also listed).

Mandiant releases Net-NTLMv1 rainbow tables to accelerate deprecation: In a January 16, 2026 Google Cloud blog post, Nic Losby (Mandiant) says Mandiant is publicly releasing Net-NTLMv1 rainbow tables, asserting the dataset enables defenders/researchers to recover keys in under 12 hours using consumer hardware costing less than $600 USD.

That’s all for today. Thank you for reading this issue of Deep Engineering. We have some really exciting things planned for Deep Engineering members in 2026 and we can’t wait to tell you all about it very soon.

We’ll be back next week with more expert-led content.

Stay awesome,

Divya Anne Selvaraj

Editor-in-Chief, Deep Engineering

If your company is interested in reaching an audience of developers, software engineers, and tech decision makers, you may want to advertise with us.

Stellar breakdown of how decompsition actually works in practise. The video processing pipeline example made that "back-pressure" concept super concrete for me - I had struggled with that in a similar sytsem few months back where output buffering would kill performance and didnt think to just add a simple buffer queue. The multi-dimensional abstraction cost framework is gold too.